Introduction

Growing Up Absurd is a 1960 book by Paul Goodman on the relationship between American juvenile delinquency and societal opportunities to fulfill natural needs. Contrary to the then-popular view that juvenile delinquents should be led to properly regard society and its goals, Goodman argued that young American men were justified in their disaffection because their society lacked the preconditions for growing up, such as meaningful work, honorable community, sexual freedom, and spiritual sustenance.

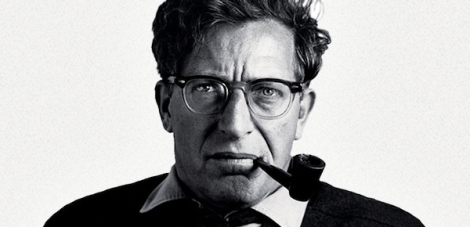

Paul Goodman

Paul Goodman (1911–1972) was an American writer and public intellectual best known for his 1960s works of social criticism. Goodman was prolific across numerous literary genres and non-fiction topics, including the arts, civil rights, decentralization, democracy, education, media, politics, psychology, technology, urban planning, and war. As a humanist and self-styled man of letters, his works often addressed a common theme of the individual citizen's duties in the larger society, and the responsibility to exercise autonomy, act creatively, and realize one's own human nature.

Born to a Jewish family in New York City, Goodman was raised by his aunts and sister and attended City College of New York. As an aspiring writer, he wrote and published poems and fiction before receiving his doctorate from the University of Chicago. He returned to writing in New York City and took sporadic magazine writing and teaching jobs, several of which he lost for his public bisexuality and World War II draft resistance. Goodman discovered anarchism and wrote for libertarian journals. His radicalism was rooted in psychological theory. He co-wrote the theory behind Gestalt therapy based on Wilhelm Reich's radical Freudianism and held psychoanalytic sessions through the 1950s while continuing to write prolifically.

His 1960 book of social criticism, Growing Up Absurd, established his importance as a mainstream cultural theorist. Goodman became known as "the philosopher of the New Left" and his anarchistic disposition was influential in 1960s counterculture and the free school movement. Despite being the foremost American intellectual of non-Marxist radicalism in his time, his celebrity did not endure far beyond his life. Goodman is remembered for his utopian proposals and principled belief in human potential.

Background and Synopsis

Following World War II, amidst underlying fears from nuclear proliferation, American radicals began to describe increasingly regimented societal expectations as "the organized system" by the mid-1950s. Themes of rising defiant, restless, disaffected youth culture seceding from social order became popular in the media, between teenage gangs, bohemian beatniks, and the more reckless working-class youth. Growing Up Absurd follows 1950s sociological critiques like The Organization Man but instead of focusing on business personnel, focuses on the collateral damage. Growing Up Absurd author Paul Goodman disagrees with the then-common view that the solution for youth disaffection was to bring the youth to properly regard society and its goals. Siding with the youth, he argued that the young already understood and rejected society's overorganized and unimportant goals.

In Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized System, Goodman blames American culture and value systems for the rise of juvenile delinquency in the late 1950s. He argues that both urban juvenile delinquency and the beatnik subculture were responses of rebellion against the organized system. Goodman focuses on young men who, he argues, were justified in their rebellion against a society lacking in meaningful vocation, honorable community, sexual freedom, and spiritual sustenance.[6] Youth require these qualities in their society in order to grow up and develop their social and moral identities.

Work becomes meaningless, Goodman argued, when it focuses on role, procedure, profit, rather than love, style, interest, use. Since advertising spurred artificial demand for useless goods, corporate jobs had become abundant but were unfulfilling, without a sense of purpose or service, and climbing to corporate power through routine, bureaucratic jobs was contrary to the ideals of purposeful vocation. Worse, this mechanical state of affairs was widely accepted as inescapable or the natural conditions of work, for which Goodman used the metaphor: an "apparently closed room" fixated on a "rat race". Those that did not conform, he writes, were cast aside as "drop-outs" with inchoate frustration. Goodman refers to this corporate takeover as "sociolatry", that citizens had traded the simple pleasures of daily life for the securities of living under an affluent, mechanized order. To Goodman, this trade-off was "absurd": even with better schools and staffing, it would still be wrong to "socialize" youth into role responsibilities detrimental to human nature. If societal aims are wrong, the urge to socialize children becomes circular and self-serving. Goodman asks, "Socialization to what?" Those seeking to correct delinquency, he wrote, should instead improve society and culture's opportunities to meet the appetites of human nature. Goodman faulted social critics, including himself, and academic sociologists for being content with studying this system without endeavoring to change it. He held that attempts to mold human nature to social order would backfire and that, given the chance, "freedom and meaning will outweigh anomie".

To create a society worthy for youth to want to join, Goodman resolves, certain "unfinished" revolutions must be brought to their conclusion on topics including brotherhood of man, democracy, free speech, pacifism, progressive education, syndicalism, and technology. He implores readers to seriously pursue these ideals, to not just rebel but to do so politically.

The book was a best-seller, with 100,000 copies sold in three years and half a million paperback copies printed by 1973. Growing Up Absurd enjoyed wide readership among the New Left and across 1960s college campuses. Goodman's ideas became popular with student activists and it was said that every activist at Berkeley had a copy, even if few read the full text. Americans had seen isolated headlines on juvenile delinquency but had not noticed the similar patterns between both urban and beatnik revolt against the organized system. To this public, Goodman's literary executor Taylor Stoehr recounted, Growing Up Absurd was "a revelation". Chapters from the book were republished in radical and mainstream magazines. Commentary readers responded positively and the revamped magazine's editor Norman Podhoretz credited the strong response to Growing Up Absurd's serialized extractions for Commentary's quick ascent. Following the book's success, Goodman's publisher expressed interest in reprinting his Communitas. Extracts from Growing Up Absurd later ran in the Evergreen Review and many edited group volumes. Unlike the American response, its release was panned in the British press.

Growing Up Absurd was revelatory to readers who had not considered but wanted to believe that work and ideals were connected. To this new audience, Goodman read as both fresh and old-fashioned: a contemporary man of letters's unabashed advocacy for a moral culture with traditional values of faith, honor, vocation. Goodman's discussion of the "rat race" and worthwhile work too resonated with college students, who had similar realizations, but was more distant to adults who had grown accustomed to the American nature of work. The book's advocacy for youth's sexual freedom was shocking to older readers and some accused Goodman of using the book to argue for acceptance of sexual deviance.

Contemporaneously, public intellectual John K. Galbraith described Goodman's book as hard to read from its title to its appendix, in contrast to the increasingly commonplace slick and superficial mass market works of criticism. Dwight Macdonald too lamented Goodman's writing being less clear than his thinking, though Macdonald admired Growing Up Absurd among Goodman's oeuvre. Literary critic Kingsley Widmer described Goodman's rhetoric as varying between righteousness, condescension, and magnanimity. As one later reviewer put it, Goodman was not supporting youth as much as psychologizing them and their societal alienation.

Some critics focused on Goodman's ability to offer solutions. That youth want meaningful work, said The Times Literary Supplement, is a tautology. While it is easier to puritanically agree with Goodman's assessment of societal downfalls, the reviewer said it is harder to ascertain why we agree with these aims yet cannot seem to achieve them. In this way, Goodman banked too heavily on the miraculous changing of minds rather than meeting people where they were. Galbraith's New York Times review considered Growing Up Absurd a "serious effort" despite not offering robust solutions.

On the occasion of the book's 2012 reprint, one retrospective reviewer considered the book's core issues of corporate greed and spiritual barrenness as being more pronounced than 50 years prior.

Legacy

Fueled by the changing desires of the times, including a willingness to address societal issues, Growing Up Absurd transformed Goodman's outcast career and brought him public fame as a social critic and educational theorist. He emerged from the book with attention he had long sought, including a college lecture circuit and a public role both literary and in school reform. Some of Goodman's ideas have been assimilated into mainstream, "common sense" thought: local community autonomy and decentralization, better balance between rural and urban life, morality-led technological advances, break-up of regimented schooling, art in mass media, and a culture less focused on a wasteful standard of living. His systemic societal critique was adopted by 1960s New Left radicals and an emphasis on moral life subsequently became part of the New Left's aspirations. Goodman bridged the 1950s era of mass conformity and repression into the 1960s era of youth counterculture in his encouragement of dissent. Goodman became a popular guest speaker both for the book's resonance with 1960s youth and his criticism of the youth movement's excesses.[5] He was invited to lecture at hundreds of colleges.

Goodman's outré expressions on art, politics, and sexuality were misinterpreted by his followers as acts of defiance, intentionally flouting a sick society's norms, but they were more accurately described as Goodman's own refusal to acquiesce. Both interpretations built his affinity with the youth. While some criticized his flattery of his young followers, Goodman often reminded his young audiences of their inexperience and encouraged them to pursue mastery if they wanted to make a better world. Part of Goodman's appeal as a "Dutch uncle" was his reminder that their cultural birthright once featured ideals, acts, and people worthy of pride.

Many specific details of the book soon became dated. While youth gangs persisted, juvenile delinquency as a topic did not and the disaffected beatniks successively traded favor for hippies and punks. Cold War-era touchpoints pervade the book. Goodman's discussion of poor youth focused on socioeconomic needs and not racial conflict. Goodman's primary intention was to show how youth issues reflect their parent society, not to provide a comparison of such issues across eras. As criticism of American society, Growing Up Absurd appeared mild by the end of the decade, according to Merle Miller.

Goodman's patriarchal assumptions about gender and treatment of women, exemplified in his focus on "man's work" and the inherent fulfillment of motherhood, were rebuked in early reviews and the following decades. In particular, he wrote that the book focuses exclusively on men and their careers because women, having the capacity for childbirth, did not need a career to justify their worth. By his literary executor's account, Goodman was "blinded in this area", having ignored the role of women's own fulfillment and extrafamilial autonomy in his description of a fully developed human nature. Retrospective reviews reproached Goodman's analytic exclusion of women and one cited it as sufficient reason to not want for a "Goodman revival". Goodman's analysis of men similarly narrows to "manly" lad culture, excluding those from upper-class or non-urban backgrounds.

Looking retrospectively at Goodman's career, literary critic Kingsley Widmer panned Growing Up Absurd as rough, rambling, and mediocre despite its insights and sociological vision. Overall, Widmer considered Goodman's analysis of vocational and community issues to be unserious, and Goodman's thoughts on decentralization and schooling to be better expressed in other works. Growing Up Absurd's main contribution, Widmer contended, was in focusing public attention "on the discontents of the young and the lack of humane values in much of our technocracy". Widmer felt that Goodman's subsequent "public gadfly" appearances had merit and that the practical idealism he wanted for the young was partially realized in the 1964 Berkeley Free Speech Movement. As 1960s campus rebellions suggested the possibility of greater change, Goodman and the youth shared mutual sympathies for several years in which he was often invited to their colleges to speak.